Climate and sustainability policies, how are they related and why are they essential for the future of the planet?

Climate change is a phenomenon which has been scientifically observed for several decades, but it was not until the 1980´s that the term became widely popular and it has been growing ever since. Nowadays, not a week goes by without a new alarming headline appears, warning of record temperatures, decreasing rainfall, and the more frequent and damaging natural disasters.

Against this backdrop, mass media and public awareness of climate change has increased and, consequently, the pressure on governments and companies to establish more effective policies. Thus, climate and sustainability policies are created as actions and measures adopted by companies and policy-makers to face the climate change challenges and foster a sustainable future.

Although it was in 1972 when the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) was created at the 1st United Nations Conference on the Environment, concern for environmental security is not a recent topic, but it is estimated that as early as 1750 b.C the Mesopotamian Hammurabi Code established penalties for those who damage the nature.

From then until today, climatic science has changed a lot and, currently, the Conference of the Parties (COP) are held annually. They are summits held by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in which the 197 member parties reach a consensus on climate measures for the coming years. Out of the 27 COPs that have been held, the most relevant have undoubtedly been COP3 or the Kyoto Protocol and COP21 or the Paris Agreement.

Climate policies are mainly focused on cutting Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions, which are the major drivers of global warming. To achieve this goal, governments promote renewable energy sources, improved energy efficiency as well as independence from fossil fuel in the main economic sectors (e.g. transport, buildings and industry).

Climate policies ofthen have a specific objective when they are implemented, but they might sometimes generate unexpected effects, both positive (co-benefits) and negative (trade-offs). These co-benefits may not only be reflected in the environmental situation, but can also generate economic and even social benefits.

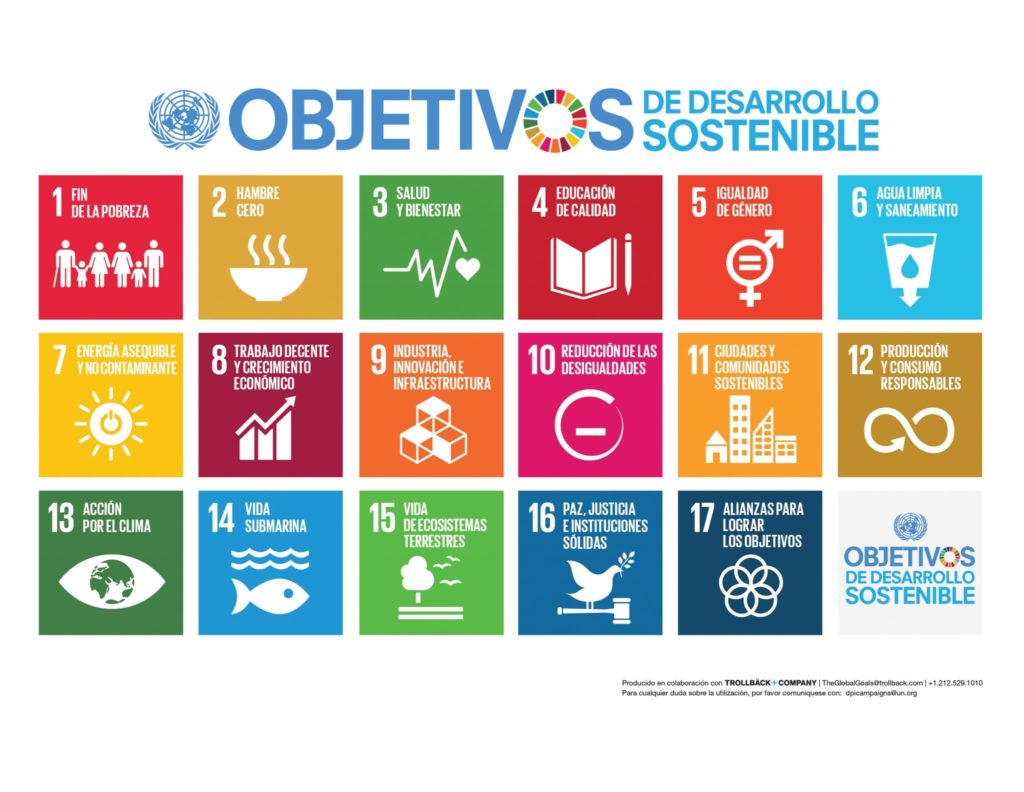

This interrelationship among economy, society and environment eas not taken into account until the emergence sustainability concept. Sustainability policies focus on promoting the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which are a total of 17 specific targets that address global challenges in the three basic pillars: environmental protection, social development and economic growth.

Though the application of climate measures in the most “traditional” sectors is essential to reduce our environmental impact, both policy-makers and the society have realised that a deeper redesign of our daily habits is needed. As a result, new regulations are continuously promoted in order to shift consumption trends and even to implement new approaches to educate future generations.

Nevertheless, all that glitters in not gold and it should be borne in mind that sustainability and climate policy implementation might be a complex process that requires a careful planning and assessment of the expected effects. Therefore, how can policy-makers be sure to establish a measure if there is a possibility of further damage? This is where “Integrated Assessment Models” (IAMs) are introduced.

IAMs are analytical tools for assessing and estimating the impacts of diverse climate policies in various areas such as the economy, the environment or the social awareness, by selecting which sectors and regions to focus on. With these models, policies can make scientifically supported decisions to address climate change or they can use them to justify previous measures.

The usefulness of IAMs is immense as long as they are well-used, but if the right optimal conditions are not met, they can become simply incomplete representations of the future. The correct functioning of these models requires the effective involvement of politicians and other stakeholders in the IAM development stage, as well as the correct definition of the policy to be modelled (what is the issue to be addressed and the objective of its implementation, what is its spatial and temporal resolution, etc.). Once these conditions have been met, it is essential to ensure that the chosen policy and model are compatible, as not all IAMs have enough capacity to forecast the impact of such a measure, either because it does not include the sector of application, because the geographical location cannot be specified, or because the temporal horizon is too long to be considered by the IAM. Currently, the efforts are focused on creating IAMs with greater diversity and capacity to implement policies that are not only related to the economy, but also to social and environmental factors.

At CARTIF we have been actively involved in IAMs for a long time and, in fact, together with our colleagues at UVA, we have developed an IAM called WILLIAM. We are also involved in several European projects, such as IAM COMPACT or NEVERMORE, which aimed at improving the assessment, transparency and cosistency of models.