We all know that Artificial Intelligence (AI) is being successfully applied in sectors such as medicine, industry, and mobility, where there are millions of data points, images, and models with which to train increasingly accurate algorithms. However, when it comes to Cultural Heritage, the situation is quite different.

Heritage assets (monuments, artworks, archaeological sites, or historical archives, among others) are fragile and, in many cases, irreplaceable. There are no large datasets from which to derive the thousands or millions of examples needed to “feed” an AI system. Each heritage asset has its own architectural, material, conservation, and historical particularities that make it unique. This scarcity of data turns the application of AI techniques, as used in other fields, not only into a challenge but into a real difficulty.

Moreover, even when enough data exists to build a useful knowledge base, there is often reluctance to share it, let alone make it public. In many cases, information about the real state of conservation of an asset, whether movable or immovable, is considered sensitive or confidential. Revealing deterioration, vulnerabilities, or pathologies could have unintended consequences, ranging from legal or security issues to economic or reputational impacts.

Even so, AI can help extract maximum value from the available information by combining data from multiple sources: technical reports, scientific analyses, surveys, 3D models, historical images, or even expert insights.

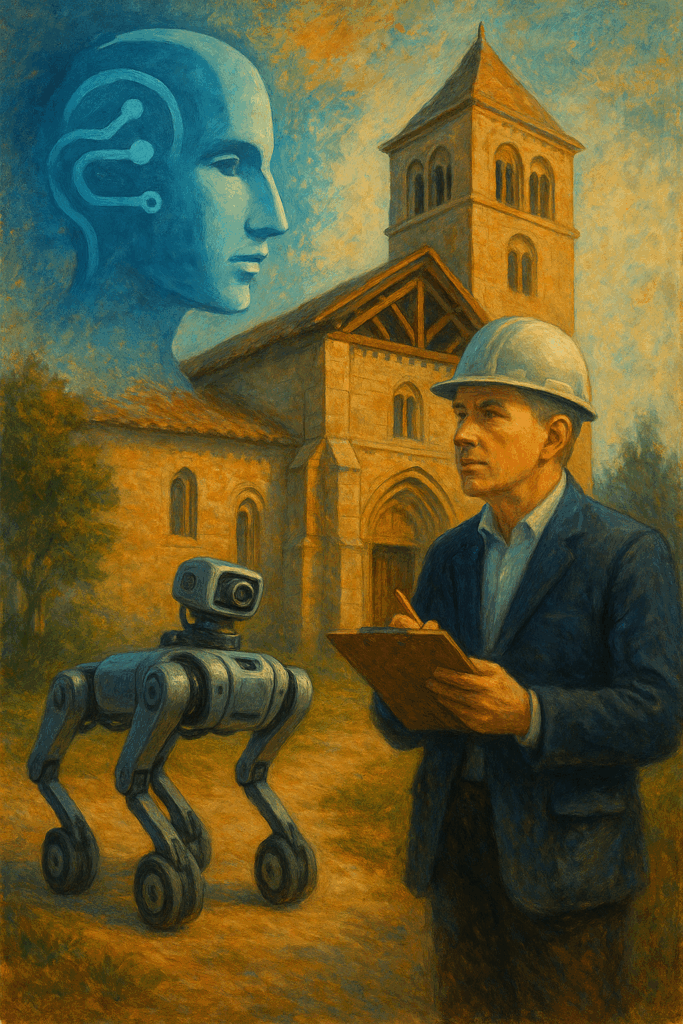

What is very clear is that, unlike other fields that will be dominated by AI, in Cultural Heritage it will never replace the human expert. Decision-making regarding the conservation or restoration of an asset requires deep contextual knowledge, sensitivity (we’ll talk another day about what this means), ethical judgment, and creativity, qualities that no machine can replicate.

However, what AI can -and inevitably will- do is support specialists: analyzing volumes of information that used to take weeks of work, detecting patterns, or proposing hypotheses about the behavior of materials, artworks, or entire buildings under different scenarios. In short, it can offer professionals an integrated and rapid view that enables them to make more informed decisions.

Looking to the future -which, in the case of Cultural Heritage, always means the long term- as more digital data is generated about heritage assets (3D scans, photogrammetric records, images in various spectral bands and resolutions, chemical analyses, or sensor data for preventive conservation), opportunities will grow. And they will do so exponentially. But always following a fundamental principle: AI is a tool to assist conservation, not a substitute for the human judgment that ensures our cultural legacy remains alive, understandable, and authentic.

CARTIF is already working in this direction alongside organizations that play a key role in the research, protection, conservation, restoration, and dissemination of Cultural Heritage. Projects such as iPhotoCult at the European level -where the applicability of AI to assess the structural integrity of historic timber roof frames inspected by a robotic dog in the Church of Nuestra Señora de la Asunción (Roa, Burgos) as a reference- will be evaluated. Likewise, the recently approved MINERVA project in Spain, which will digitize the processes of technical inspection of historic buildings defined in the previous ITEHIS project (recently presented to the Spanish Standardization Technical Committee for Conservation, Restoration, and Rehabilitation of Buildings), will contribute business and expert knowledge to guide how AI can best be oriented in this field.

There’s a long road ahead, but step by step. Shall we walk it together?”

- Artificial Intelligence and Cultural Heritage: A Promising Alliance (With Nuances) - 7 November 2025

- The black gold of Castilla y León: its Cultural Heritage - 5 December 2024

- Talking about everything visible and invisible (II) - 30 August 2024