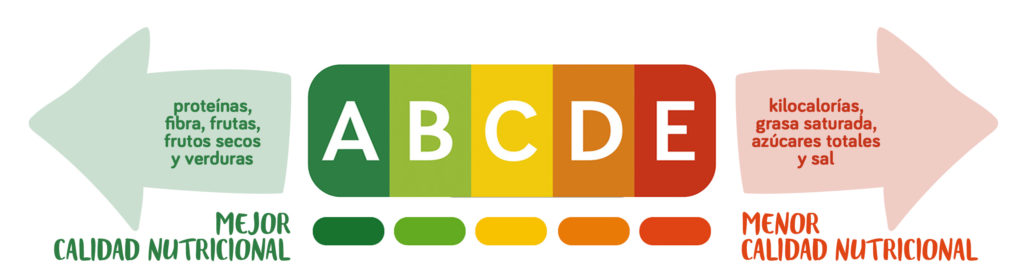

NutriScore, is a nutritional traffic light intended to help consumers make healthier buying decisions by providing information on nutritional quality at a glance. It does this by using a algorithm that gives a lower (healthier) score for protein, fibre, fruit, nuts and vegetables and a higher (less healthy) score for kilocalories, saturated fat, total sugars and salt. Based on this score, the product is given a letter with the corresponding colour code, from the healthiest which would be green (letter A) to the least healthful which would be indicated by the colour red (letter E).

But not everything is perfect in the world of the colourful algorithm. Since its birth in France (2017), it has been the subject of numerous criticisms arguing that the NutriScore not only fails to meet the objectives for which it was created but is even misleading for consumers. As expected, we are facing a divided Europe. On the one hand, the governments of France, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Belgium, Luxembourg and Germany have adopted the Nutriscore label on a voluntary basis. However, Italy considers that such labelling poses a risk to products “made in Italy” and to the Mediterranean diet, and has even presented to the Commission an alternative to NutriScore called NutrInform (which has also been widely criticised). Major food multinationals such as Nestlé, Kellogg’s and Danone have already implemented NutriScore in their own brand lines and some of the largest retail chains such as Carrefour, Erosky, Aldi and Lidl have also included NutriScore in their own brand products.

The pro-NutriScore group argues that it is an easily interpreted tool that can encourage healthy food choices and motivate industry to reformulate its products. By contrast, another group sees the NutriScore as an unfair system, which may discriminate against certain categories of food, as it does not include comprehensive nutrient information and is not based on the reference intakes of the average consumer, leading to an unbalanced diet.

The NutriScore also fails to convince the European Commission. In fact, in its Farm to Fork strategy published in March 2020, the Commission faces the challenge of implementing a single mandatory labelling system across the EU, by the last quarter of 2022, but has so far not committed itself to the NutriScore. In fact, it has proposed to launch an impact study on the different types of front of pack labelling.

Despite all this variety of opinions, today the NutriScore is one of the most widely accepted front labels in Europe and the one chosen by Spain for implementation during the first quarter of 2021.

In this situation we must not forget that the most important thing is to inform (not influence) the consumer. This situation is reminding me of what happened with Regulation 1924/2006 whose initial objective was also very worthy, as it was published to protect consumers on nutrition and health claims on food. That was a Regulation under strong pressure from the food industry which did not take the consumer into account. In fact, to this day, consumers are still not aware of the difference between a “fat-free”, “low-fat” or “reduced-fat” product, to name just one example. It was a regulation made “for” and “by” the food industry and which in my opinion has not guaranteed consumer protection either. At the very least, the NutriScore would expose a regulation that is allowing a fried roll filled with vitamin D enriched cream to claim that it “contributes to the normal functioning of the immune system”. However, the NutriScore is also being used as a marketing tool by the food industry, and the algorithm has even been modified to improve the rating of certain products.

One of the main criticisms of NutriScore is that products with low nutritional value may give the impression of being healthy after reformulation. In my opinion, the NutriScore would actually be continuing a situation that Regulation 1924/2006 has not been able to resolve. We should focus on health policies by reformulating those products with too much salt, saturated fat and sugar so that consumers can actually make healthier choices.

We already know that NutriScore is not perfect, in fact no labelling system will ever be perfect in isolation. In parallel, complementary nutrition information systems will need to be put in place. Nutrition education will of course be essential for any labelling system to be effective, but here the food industry really needs to lose its fear of being more transparent. Marketing departments must understand that including “sodium palmitate” (Latin name) or “elaeis guineensis” (name of the plant) as an ingredient instead of “palm oil” is not transparent and can confuse even a PhD in nutrition.

In the food area of CARTIF during 2021 we are preparing business initiatives related to the improvement of the nutritional profile of certain foods and actions aimed at improving nutritional labelling so that consumers can make more informed choices.

- Waiter! One of dung beetles! - 10 February 2023

- Attention: NutriScore Traffic Light! We have a huge mess - 14 January 2021

- Acrylamide has a special ‘COLOR’ - 23 January 2019