Environmental concern and awareness linked to the expected population growth, and with it the increase in demand for food and the need to ensure the sustainability of resources through more efficient processes has led to a change in the consumption trends.

Consumers, increasingly concerned about health and the need to look for more natural foods, are leaning towards diets with less meat consumption, and even veggie diets (vegan, flexitarian and vegetarian), which ultimately translates into an increase in the search for alternative plant-based proteins and the generation of new plant-based foods.

Spain has 5.1 million veggies, rising from 8% in 2017 to 13% in 2021, representing a 34% growth in the veggie population in just 4 years. Moreover, a 56% of consumers indicate that they have bought at least one veggie brand simply out of curiosity due to the increase in the number of these products.

It is becoming increasingly common to find alternative products made from plant-based proteins on the shelves. Plant-based products range from plant-based alternatives to milk, the well-known plant-based drinks, which top the list of the most popular products, followed by meat analogues, but also alternatives to eggs, cheese, fish and their respective by-products.

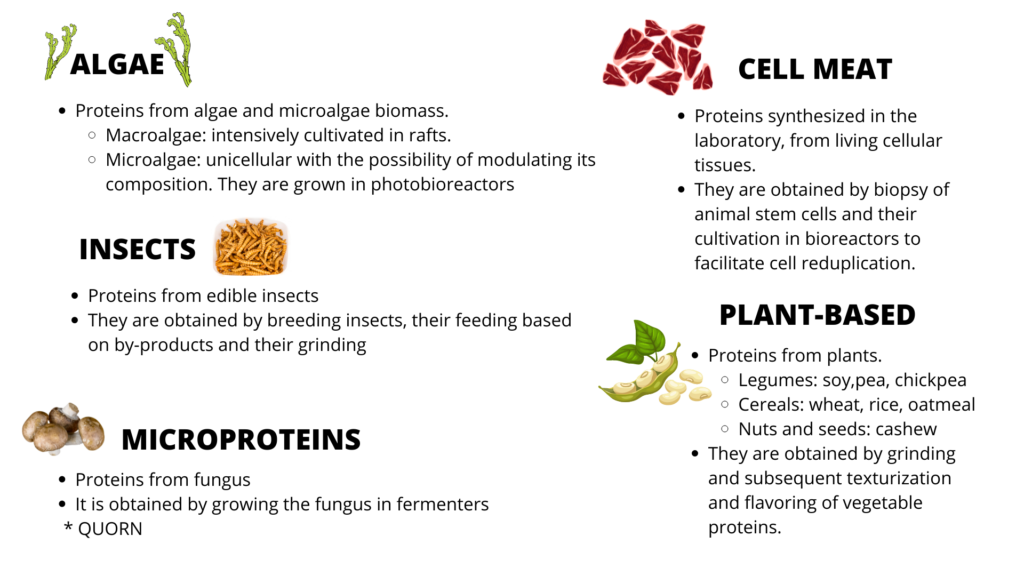

To better understand how these products are obtained, let´s take a look at the most commonly used raw materials today, which include insects, algae, microproteins, vegetable proteins (legumes and cereals), cultured meat, which can be subjected to different processes such as fermentation, extrusion or 3D printing and which are intended to replace animal.

More extended and accepted raw materials are vegetable proteins, coming from legumes and/or cereals. With these vegetable proteins alternatives, the already known alternatives to meat products are made, such as meat analogs, meat substitutes, meat imitators or meat-without meat. All these terms makes reference to food products with sensorial characteristics, taste, texture, appearance and nutritional value similar to traditional meat products.

The most widely used and accepted raw materials are vegetable proteins from legumes and/or cereals. These vegetable proteins are used to produce the well-known alternatives to meat or meat-free meat products. All these terms refer to food products with sensory characteristics, taste, texture, appearance and nutritional value similar to those of traditional meat products.

Despite the increasing supply of meat analogues, there are still limitations to their widespread use, the main one being related to sensory properties. To ensure the success of these products, the use of plant-based proteins is not enough, as consumers are not willing to sacrifice the sensory experience. This is why the food industry is constantly working to improve the production of these products, developing and optimising technologies and processes in favour of high organoleptic and nutritional qualities. In this sense, extrusion technology for obtaining alternative protein structures to meat is one of the technological lines with the greatest potential.

Extrusion is a very versatile technology based on the application of high temperature and short times, where ingredients are continuously treated and forced through a matrix that forms and texturises them, producing several simultaneous changes in the structure and chemical composition of the ingredients through the application of thermal and mechanical energy, allowing a wide range of products to be obtained.

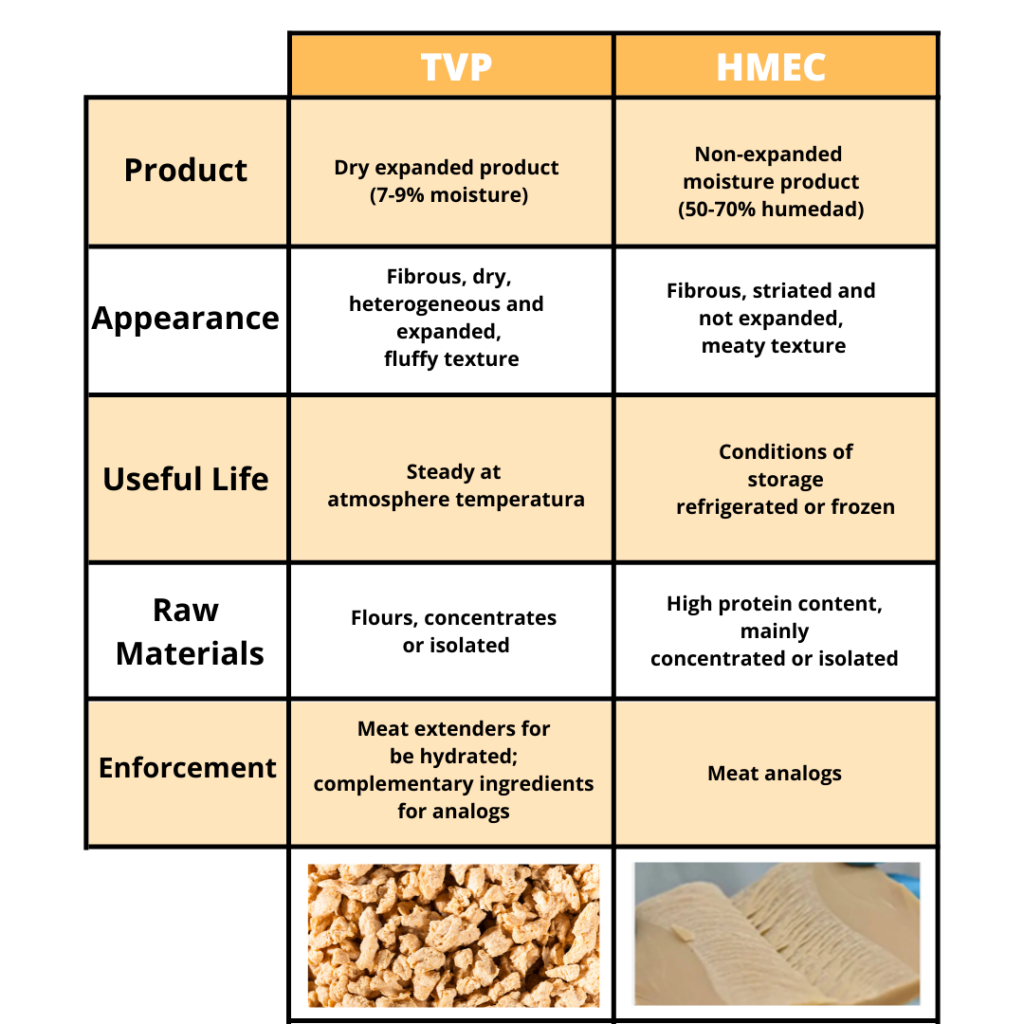

To learn a little more about this process and how it acts on vegetable proteins, it is necessary to differentiate the two types of routes that extrusion technology offers to obtain meat analogues. On the one hand, high moisture extrusion (also known as HME, high moisture extrusion), makes it possible to obtain non-expanded fibrous products that imitate the texture and mouthfeel of meat products. Therefore, they will be the protein base for the production of a meat analogue. On the other hand, dry extrusion produces the so-called textured vegetable protein (TVP), which is characterised by its expansion and requires subsequent hydration prior to use.

Since high-moisture extrusion creates a product with a meat-like structure, let’s see what actually happens to vegetable proteins during this process called texturisation:

It could be explained as a two-stage process; firstly, the protein is in its native state, with a complex structure and without access to its functionality. When heat and shear forces are applied during cooking, a denaturation of the protein takes place, losing its native structure and leaving the binding sites for new bonds accessible, which facilitates that in the second cooling stage, the protein reorganises itself by forming new bonds, giving rise to a product of a fibrous nature.

The greatest challenge of these processes is at the innovation in the use of extrusion-texturization technology combined with different blends of vegetable proteins to obtain improved textures.

This technology involves a double challenge: on the one hand, the choice of raw materials is a key parameter, being necessary to choose the appropiate vegetable protein source capable of providing the best characteristics to the final product with a good behaviour during processing and, on the other hand, to achieve and optimise the process conditions by adjusting the variables of each of the parameters to achieve the desired texture. Therefore, to achieve a better texture in mthe following must be taken into account: the choice of raw materials, the protein source, the protein content-isolate, concentrate, flour and the choice of conditions for the process parameters.

In short, obtaining products similar to those of animal origin by incorporating alternative protein sources such as cereals or legumes, and even algae, insects or microproteins, is one of the challenges facing the food industry. Although extrusion technology allows new plant-based products to be obtained, it is necessary to continue developing this technology in order to achieve the “perfect” analogue that meets all the requirements in terms of texture, taste and nutritional properties.

At CARTIF we work to integrate and optimise the texturization process with different ingredients and their mixtures, in order to obtain meat analogues with the best properties. An example of this, is the Meating Plants projects where we research the use of legume proteins to improve the quality of meat analogues.

- New challenges in plant-based food - 24 June 2022