Today I would like to talk to you about a problem that is increasingly being discussed, but which still surprises many people: what happens to the blades of the wind turbines when they are no longer useful? Because yes, they also “retire”, and when they do, they generate waste that is difficult to manage.

We all agree that wind energy is a marvel. It´s clean, renewable and a great ally against climate change. But, like almost everything in life, it also has its B side. The first thing that comes to mind when we think of a wind turbine, are those huge blades spinning in the wind to give us electricity without polluting. And yes, that´s great…while they´re working. The problem comes when these blades reach the end of their useful life and have to be disposed of. Then, what was a brilliant solution becomes a headache. And a big one at that. Becasue these paddles are designed to resist everything: wind, rain, sun, snow…That´s why they are light and very resistant, thanks to the materials they are made of: composite materials (fibreglass and resins) and balsa wood. The disadvantage is that, precisely because of these resistant materials, they aren´t easy to recycle. And of course, the question is inevitable: what we do with them?

For you to have an idea of the size of the problem, at the end of 2024 in Spain alone, there were 1,371 wind farms spread across 828 municipalities, with no less than 22,210 wind turbines and more than 65,000 installed blades1. And watch out, because almost 35% of these wind turbines were commissioned before 2002, which means that they have already exceed 20 years of useful life, which is usually between 15 and 25 years. In other words, in the coming years we will be faced with a veritable avalanche of blades that will have to bel dismantled and managed.

“In Spain, at the end of 2024, there were 1,371 wind farms with 22,210 wind turbines and more than 65,000 installed blades”

What if we look beyond our borders? In Europe, it´s estimated that by 2050, the volume of blades waste will generate more than 2 million tons per year, and that the cumulative total could reach 43 million of tons2. All these tonnes are best understood if we remember that a single badle can measure more than 50 metres and weigh around 6 tonnes- almost nothing! Tons and tons of badles that we can not simply sweep under the carpet (or rather in the landfill). And no, that´s obviously not a good option, nor is it sustainable. And the most worrying thing: there is still no generalised solution for all that material.

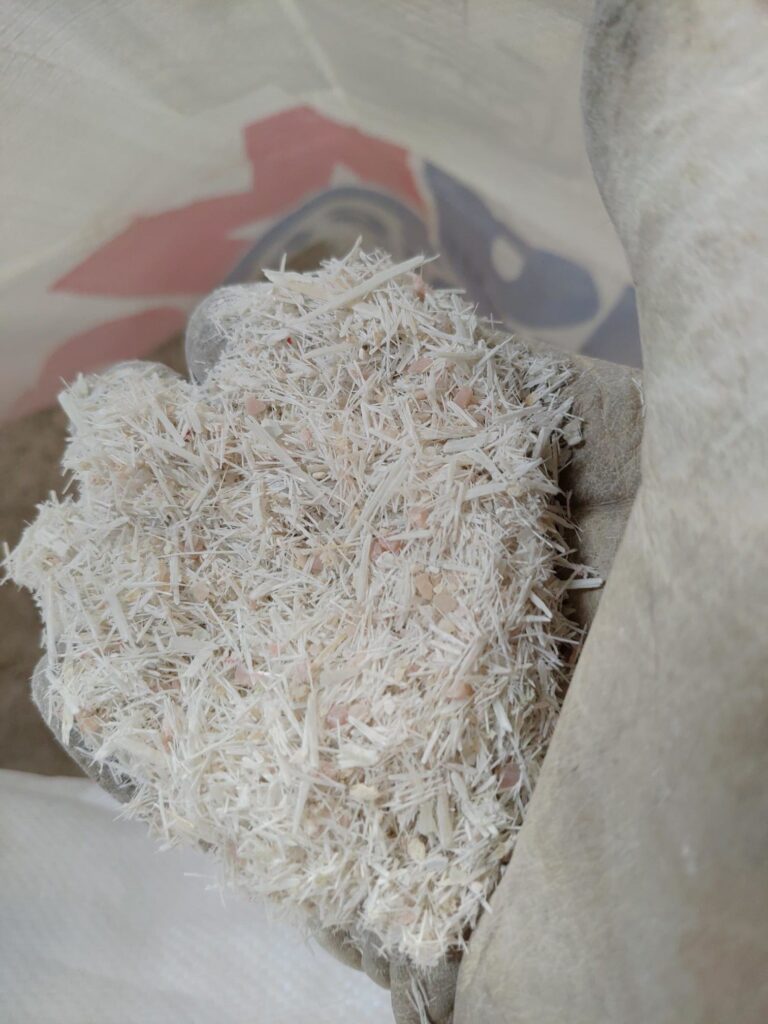

And in this is where our work comes in. At CARTIF, we have been working precisely on this, on finding a second life for these blades. One of the projects in which I have participated is called LIFE REFIBRE, and in it we have developed equipment to mechanically recycle these blades. What we do is crush them under very controlled conditions to recover the glass fibre they contain. And what do we do with that fibre? Well, we have incorporated it into asphalt road mixes. And it works! It provides extra properties that improve the durability of the road surface. So not only do we prevent this waste from ending up in landfill, but we also give added value to the roads, being a clear example of circular economy.

What is interesting is that there is no a single way to recycle these blades. In addition to mechanical recycling, at CARTIF we have also investigated other more advanced and promising ways, such as pyrolysis and chemical recycling. Pyrolisis is a thermal process in which the blades are heated in the absence of oxygen, which allows the resins to be broken down without burning them. This process produces gases, liquids and glass fibres. The gases and liquids can be recovered energetically, and the glass fibres are practically free of resin. At CARTIF we have worked on optimising the process conditions to maximise fibre recovery with its mechanical properties as intact as possible. On the other hand, chemical recycling consists of applying specific reagents to selectively degrade the resins and thus separate the glass fibres without damaging them and better preserving their structural properties. This allows them to be reused in higher valued-added applications, such as new composite materials, automotive componentes, etc. Both techniques present challenges, such as energy efficiency, by-products recovery or industrial scalability, but their potential is huge. Obtaining glass fibres without resin opens the door to reuse them in much more demanding products. At CARTIF we continue to investigate these avenues because we firmly believe that the future lies in solutions that not only avoid landfill, but also transform a complex waste into a valuable resource.

The important thing is not to look the other way and think about what happens when the mill stops turning. Because blades are not to be uses and thrown away, nor are they to be buried in disguise. They also deserve a second life, and that is why we need solutions that are truly sustainable and circular. And, from my experience, I can assure you that you can find them. Because yes, blades also have the right to a dignified retirement…..and a sustainable one.

1 Spanish eolic association/ Eolic Report 2024. The sector voice

2 Wind energy in Europe/ 2024 Statistics and the outlook for 2025-2030

- The hide challenge of the eolic energy: what we do with the wind turbines blades? - 16 April 2025

- About recycling, celebrations and children - 4 July 2017