A growing problem: mountains of textile waste

Clothing and textile consumption has increase with the expansion of so-called “fast fashion”, giving rise to enromous amounts of waste. In Europe, the European Environment Agency (EEA)1 reports that each EU citizen purchased an average of 19kg of clothing, footwear and household textiles in 2022, up from 17kg in 2019. Furthermore, around 6.94 million tons of textile waste was generated in the EU. However, collection infraestructure has not kept pace with this growth, and most of this waste is not recovered. Only around 15% of textile waste in Europe is collected separately or recycled, meaning the remaining 85% ends up in the trash, incinerated or in landfills without any second life.

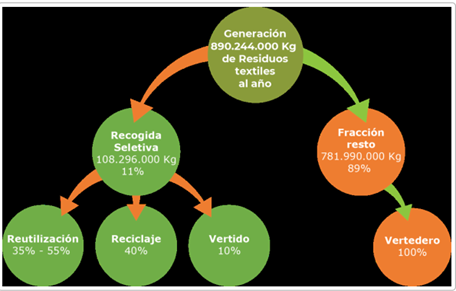

In Spain the situation is also worrying. Our country exceeds the European average in fashion consumption, with an estimated generation of nearly 900,000 tons os textile waste per year. According to the Spanish Federation for Recovery and Recycling (FER), only 11% of used clothing in Spain is collected in specific containers. This enormous waste of materials reflects the fact that the vast majority of our used clothes never find a second life.

The obstacle of fiber mixtures in traditional recycling

Why is so little clothing recycled? One of the main obstacles is the propper composition of the clothes. It is common that they are confeccionated with fibre mixture, for example, a t-shirt with 50% cotton and 50% polyester, or fabrics that combine synthetic and natural fibres. These mixtures, joint with colour and additives applied to fabrics, difficults the traditional mechanical recycling that consists on TRITURAR the used clothes to obtain reusable fibres.

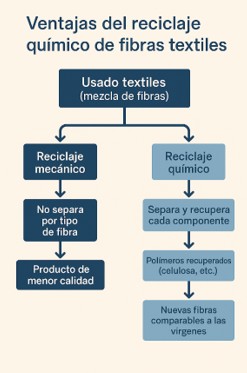

Why is clothing recycled so little? One of the main obstacles is the composition of the garments themselves. They are often made from blends of fibers, for example, a T-shirt with 50% cotton and 50% polyester, or fabrics that combine polyester with viscose. In fact, most post-consumer textile waste contains combinations of synthetic and natural fibers. These blends, along with the dyes and additives applied to the fabrics, make traditional mechanical recycling, which involves shredding used garments to obtain reusable fibers, extremely difficult.

This process requires fairly pure and uniform waste streams to be successful. If we introduce a blend of cotton and polyester into the shredder, we will obtain a mass of mixed fibers of different natures that cannot be easily spun into new, high-quality yarn. Furthermore, with each recycling cycle, the fibers become shorter and weaker. Therefore, mechanical recycling typically repurposes recovered fibers into lower-value products—a process known as “downcycling”—such as insulation, cushion stuffing, or construction materials, rather than being converted back into clothing.

When a garment contains multiple types of fibers glued together or includes complex chemical treatments, it often cannot be recycled mechanically at all, and that mixed garment ends up directly in the landfill. In short, our current garments are full of mixtures and finishes that traditional recycling can’t separate, and they end up wasted.

Chemical recycling: decompose clothes to recover materials

Faced with this problem, chemical recycling is positioned as a promising solution. Through processes such as selective dissolution or depolymerization, it allows fabrics to be broken down at the molecular level and their basic components recovered: cellulose, plastic monomers, or new regenerated fibers. Instead of shredding or melting, the raw material is “rewound” to “start over.”

Some recent examples show that this technology is already taking steps towards industrial reality. The German startup Eeden, for example, is building a pilot plant to recycle cotton and polyester blends. Its process allows for the recovery of high-purity cellulose from cotton and polyester monomers (such as terephthalic acid), which can be reused in the manufacture of new fibers.

For their part, BASF and Inditex have developed Loopamid®, the first nylon 6 recycled entirely from textile waste. Thanks to a chemical depolymerization and repolymerization process, it is possible to obtain a new polymer with comparable quality to the original, which has already been used to manufacture garment prototypes.

Although still an emerging technology, chemical recycling is demonstrating its ability to close the textile loop even in the most complex cases, and will be key to moving toward truly circular fashion.

Through circular economy in fashion

In short, chemical recycling of textile waste is emerging as a necessary and complementary solution to mechanical recycling to address the fashion waste crisis. Faced with an ever-increasing volume of discarded clothing—and, especially, the challenge posed by mixed-fiber garments, omnipresent in our wardrobes—chemical technologies offer the possibility of recovering materials with original quality, overcoming the limitations of traditional methods. Although they still need to be scaled industrially and reduced in cost, it has already been demonstrated that it is technically feasible to convert a used garment into a new one, separating polymers and removing impurities in the process.

In the future, combining better designs (longer-lasting and more recyclable garments), responsible consumption, efficient collection and sorting systems, and all available forms of recycling will be key to achieving a truly circular economy in the textile sector. In this scenario, chemical recycling will become an essential ally so that that used T-shirt we today consider waste can be “reborn” into high-quality raw materials, reducing the environmental burden of fashion and closing the textile cycle.

1 Agencia Europea de Medio Ambiente (2025). https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/newsroom/news/consumption-of-clothing-footwear-other-textiles-in-the-eu-reaches-new-record-high#:~:text=The%20average%20EU%20citizen%20bought,the%20EU%E2%80%99s%20textile%20value%20chain

2 Federación Española de la Recuperación y el Reciclaje (FER). Info Textil (2024). Estadísticas de residuos textiles en España: https://www.recuperacion.org/info-textiles/